Ok, a disclaimer from the start. I know that one shouldn't write when cross. Best always to leave it to a calmer time. But I am cross. And sad. And all sorts of other emotions.

I've also (as a result of this and a long day) just consumed a nice amount of saké courtesy of

Akashiso a friendly sushi restaurant in the town of Saintes, France.

======================================================================================

A DISCLAIMER (feel free to skip this bit)

This blog is going to have a lot of "name checks". Shout outs to various people/organisations whose work I appreciate (starting with the above purveyor of saké). This disclaimer comes in light of several long chat's I've recently had with one of the most fantastic musicians and out and out general good guys I know - Joe Walters. Mr Walters has put up with me blasting in his left ear for many a year, he's the most stunning second horn a girl could want. A good example might be a recent recording patch for

Pygmalion which we did of wonderful Mozart arias with

Sabine Devieilhe (very popular in France, but I think currently less known in the UK - coloratura to knock your socks off). The orchestra was asked to pick a note, any note, and play it LOUD - the director

(Raphael Pichon - another one to watch, more talent in his little finger than a lot of big name conductors twice, or thrice his age) wanted a "nasty" chord to prelude the famous Queen of the Night aria. Unfortunately, Joe seemed to second guess my ever move and always picked a unison to my note. Mr Walters is ridiculous good and when not playing the horn is the mastermind behind a wonderful charity bringing music to kids in India -

Songbound. Go check it out and chuck him a tenner whilst you're at it. Good work being done here. (He's also married to the most outstanding operatic soprano who just melts me every time she opens her mouth - more of later).

Anyhow - Joe and I had a number of chats about "internet etiquette" and how we feel less inclined to state

anything in case it might be misread as boasting / showing off. We'd both been working in Paris in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo killings and had felt disinclined to mention on Facebook etc that we'd been on the march incase some one out there thought we were bragging ("Look at me! I'm in Paris"). Ugh. Anyhow. BTW Did I mention the sake?

Regardless of this trepidation I've decided that there are so many good things happening and many wonderful musicians and organisations that, sod it, they're all going to get a mention. If it rubs you up the wrong way best skip the whole thing. A lot of this particular blog is about supporting one another and trying to get the message out about the amazing work that's going on so consider it part of my effort.

======================================================================================

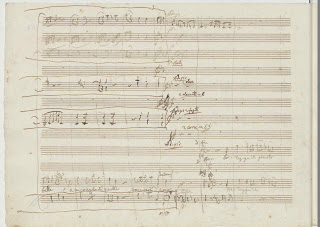

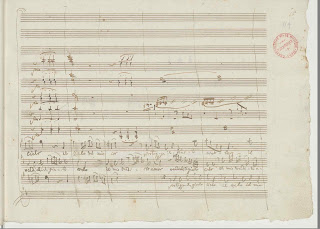

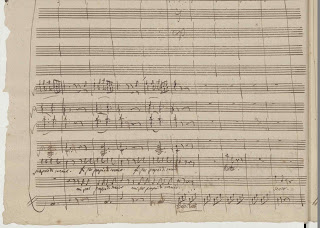

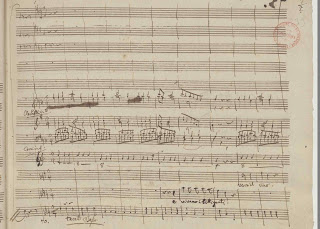

So, why am I so very cross? What pushed me over the edge was this picture a colleague shared on Facebook:

This picture really touched a nerve because I had recently learnt that my beloved

Bath Compact Discs was closing. Their owner, Steve Macallister, had recently told me that they were planning to shut up their shop and go mail order before Christmas but for them to close completely was really a terrible blow.

I'd known of Bath Compact Discs for years. Their's was the sort of shop I'd always pop into if I was in town. There used to be loads independent CD stores dotted about and it was always worth looking into as their stock would vary so much. You might stumble across something you'd never come across before purely thanks to the choices (and probably also some lucky mistakes) made by the owners. There used to be a little CD store in Parma, Italy which I have to thank for introducing me to the most wonderful

Berwald Quartet for clarinet, horn, bassoon and piano. It was the only recording they had with horn in stock, I didn't know it, I bought it and fell in love. The serendipity of browsing....

A few years back I had been on a (un-Bridget-Jones-esque) mini break in Bath with (in for a penny, out for a pound name checks) "composer

John Croft". (Sod it, his music is great) and dragged him along to Bath Compact Discs. We easily spent three figures but we came away with an amazing hoard of discs. Some stuff I really wouldn't normally buy but love. I remember the big hits of that day was a boxed set of

Stravinsky conducting Stravinsky (really exciting stuff) and a recording of above mentioned operatic soprano who makes me melt singing

Lutosławski. I didn't even know she had done this recording and blimey it's good.

It was a little while later that I began to question my Amazon addiction.

It might have been kickstarted by me doing my accounts and finding TONS of payments to Amazon and having to wade through them working out what were legitimate expenses I could claim as tax deductible (business related expenses such as CDs) and what wasn't (such as filters for the vacuum cleaner). Over the course of a year it was a lot of money. Yes, I had Amazon Prime and the "One Click" setting. If I fancied a CD or a filter for my vacuum cleaner, "One Click" and it'd be there the next day.

It may also have been me discovering that Amazon were able to sell my CDs cheaper than I could buy them. This is not the time or place for a discussion of the various "market forces" in the classical music industry. Suffice to say over the last few years I've recorded various solo discs which have (in a small niche market) been favourably received but in the greater scheme of things I'm small fry. Strike that, plankton. In Amazon terms - 361,507th in "Music". Ok, I enjoy recording the more obscure end of the horn repertoire partially because there is SO much good stuff out there and partially because I do wonder whether the world really does need another recording of the Mozart horn concerti given all this untapped wealth? From what I understand it's more due to their nanobots than their clout but Amazon can afford to sell my CDs for less than I can buy them and that kind of felt wrong.

There were rumblings of Amazon's dodgy ethics. This was before the

Panorama documentary on them. It bothered me. I try and make ethical choices as much as I can. I try and bank and shop ethically. Yes, I'm certain my various choices could be shot down in flames but I (naively?) believe that at least trying to do this is better than sticking my fingers in my ears and going "nah-nah-nah-nah-I'm-not-listening" and spending my money with the nearest/fastest/cheapest retailer....

So - I decided to cancel my Amazon Prime account and drop Bath Compact Discs a line. From the outset they were great. Here comes some more name dropping:

I wanted to buy a load of CDs by

James Gilchrist. He's smashing and I was working with him a lot around this time. He's recorded many CDs with an equally first class pianist

Anna Tillbrook, check her out as well. James and I were going to record some Schubert (

Auf dem Strom - on a horn from the

Bate Collection, Oxford) and I wanted to have a listen around how he sang Schubert before we did so. Basically, I cut and pasted my "basket" on Amazon and sent it to Bath CDs saying that I'd had enough and would rather spend my money with them.

I got a nice reply (basically saying that they couldn't possibly disagree with anyone wanting to boycott Amazon) but politely pointing out that I might not have noticed that one of the four Gilchirst/Tillbrook CDs I'd requested was actually a compilation CD containing...material from the other three discs I wanted and asking if I was sure I wanted that one as well? Oh, and by the way, did I happen to know that James had a recording of the

Britten Serenade coming out (ah, yes, the owner of Bath CDs is a horn player), did they want me to grab a copy when it came out? They were fabulous, knowledgable, prompt, helpful, a wonderful shop and I will miss them sorely.

The thing that has been bugging me about this hasn't just been necessarily the normal rants about Amazon and the tax they do/don't pay or the working conditions they impose. Many people can do that better than I can. What's bugging me is that the small independent companies in addition to supporting their local community, employing people, paying their taxes etc etc etc (aka known as the things we should all do and take pride in) supported the artists themselves.

The first time I rang up Bath CDs to give them my debit card details (oh, lord, please don't hack them now - we had an Amazon-esque set up, they had my details and I'd just email them my latest wish list - more of anon), I had been told by their owner that it'd be fine to ring after closing as he was going to be there till late as he was working on their latest batch of accounts so ring whenever I wanted. As mentioned above Steve Macallister is a fellow horn player. I actually did my FIRST EVER baroque horn date with him many moons ago so he has a lot to be blamed for. When I rang him to hand over my card details we had a lovely long chat about what was going on and he said that I should send him some CDs for his shop. At the risk of sounding ridiculous - come on, did Amazon EVER offer me THAT level of service?

But over the years it became a point of pride that anything good I heard about coming up I'd buy through Bath Compact Discs. I remember the buzz surrounding the

Tavener Choir recording of Monteverdi's Orfeo. Some of my friends were on it and the sessions had obviously been good so I dropped Bath CDs a line saying that I wanted this as soon as it came out. Yes, of course, that's not the most obscure of obscure records, I'm certain that "my little effort" wasn't going to bring a hidden gem to the eyes of what was a savvy and well informed independent record store but it just felt part of what was a nice relationship. They supported us and I tried to do the same back.

What makes me cross is this. We spend god knows how much money per year on classical music CDs. Thanks to the internet they could be coming from Lands End to John O'Groats or even further afield. The reason I think most people use Amazon is because (a) it's easy, (b) it's cheaper (see above and their nanobots) (c) they're fast.

Oh for crying out loud. Are we (a) that lazy, (b) that tight and (c) that impatient?

Some solutions:

(a) Find an independent and patronise them. Here's a

list of them. Pick one and get to know them, it's worth it.

(b) Spend A LITTLE more and see your money going into employing people, paying taxes (which benefits all of us!) and supporting the arts and the artists.

(c) Good things come to those that wait!

A final penultimate thought to share with you all:

Here is/was (*sniff*) my final list to Bath CDs:

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Joseph & Michael Haydn, Franz Xaver Gruber: Heiligste Nacht: Christmas Music (Hassler Consort, dir. Franz Raml, DG Scene MDG 614 1048-2. _

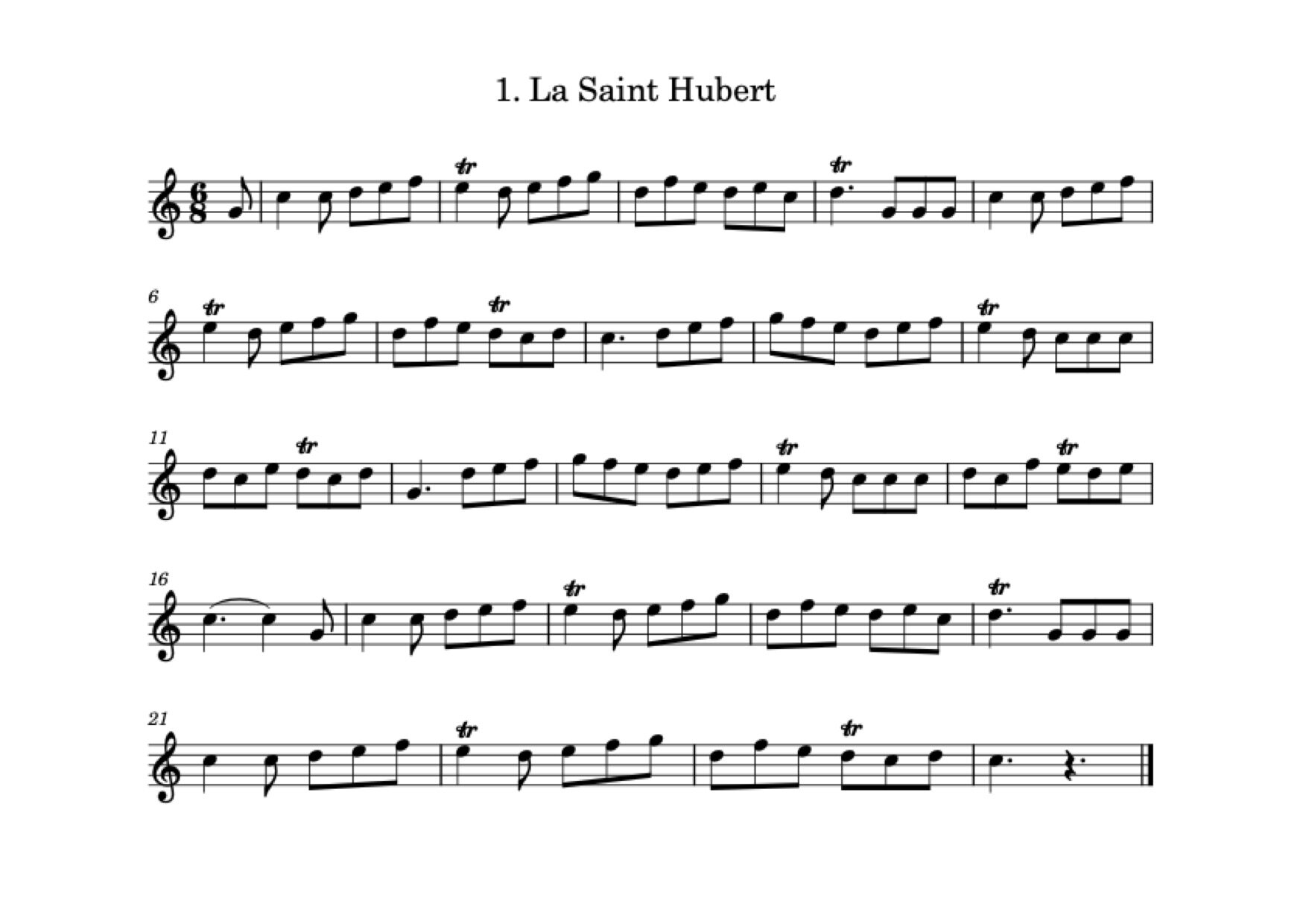

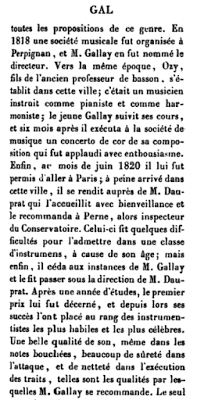

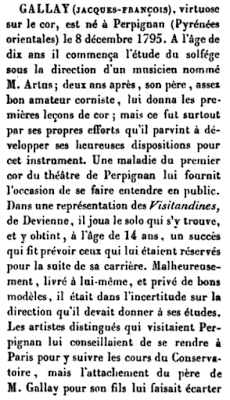

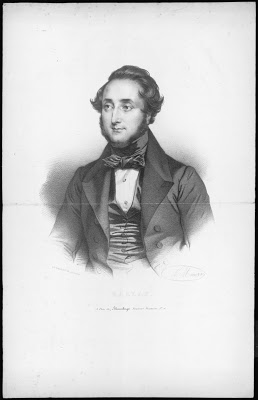

- Someone, I'm embarrassed but I forget who (I think it was one of the kickstarter backers for my recent Gallay disc, coming soon on Resonus), recommended this. If someone recommends something I tend to get it. If it's something I don't care about I download.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Nassauische Hofmusik; Franz Christoph Neubauer: Kantate 'Der Herr ist würdig', Giovanni Punto: Hornkonzert E-Dur; Giuseppe Demachi: Sinfonia Es-Dur; Johann Paul Rothfischer: Convertere Domine; Carl Ludwig +Junker: Klavierkonzert B-Dur; Kim Patrick Clow, Mark Kroll, Robert Ostermeyer, Klaus Mertens, Stephan Katte, Kantorei der Schlosskirche Weilburg, Capella Weilburgensis, Doris Hagel; 1 CD Profil PH14041; 9/13 (69'51) - Rezension von Guy Engels & Remy Franck.

- Three people in the space about a week mentioned horn player Stephan Katte. I don't know him but I rate the people who mentioned him. Steve from Bath says it's not yet available in the UK but my new source (www.abergavennymusic.com) have said they can either order it in from the States or keep an eye out and let me know if it comes out in the UK. As I say, I don't know Katte but he's getting off his backside and recording not-another-Mozart-horn-concerto so I've asked them to order it in. Good for him.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Brahms: Trios / Stransky, Schmidl, Wachter, Varga, Okada - Camerata Records (28075).

Now Steve from Bath says this is tricky. I've just finished doing a run of "La Chauve-Souris" (more commonly known as "Die Fledermaus") at the Opera-Comique in Paris with Marc Minkowski and the Musicians de Louvre Grenoble. Mr Peter Wächter, violinist with the Weiner Philharmoniker, and therefore much more knowledgable on Johann Strauss than the rest of us, was the guest concermaster. I thought he was nice and was interested in his work, googled him and it turns out he's recorded the Brahms Horn Trio so I thought I'd get a copy. Steve from Bath says it's sadly only available in Japan so maybe I can pick it up when I'm there in February.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Pip Eastop’s new Mozart / Hanover Band / Hyperion disc - CDA68097

Pip was one of my teachers. He hated me saying that he was a bit of a mentor but he does things differently and it was great as a student to be shown that there was more than one pathway into a life as a professional horn player. Yes, ANOTHER, Mozart horn concerto disc. But I can totally guarantee that this one will be unique. Steve from Bath said "The cadenza in the last movement of no.4 had me giggling out loud while I was listening to it" which is to be expected.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Edding Quartet / Northern Light - Schubert: Octet D803 & Quartettsatz D703 (Phi) - LHP015 - readily available.

A good friend and stunning musician, Nicola Boud (clarinet) along with some other excellent folk are on this. I saw Nic the other day and remembered that this was now out so wanted to buy it.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

The good news is that Steve from Bath pointed me in the direction of a number of similar shops to his. I've been in touch with

Abergavenny Music with the above list and they're on to it. (NB they don't charge P&P for CDs and DVDs). It crushed my already broken heart just a little bit when James Joseph of Abergavenny Music wrote that "My wife tells me I've been quoting them [Bath Compact Discs] as a sort of gold standard ever since we opened here in 1990!".

So I'm going to carry on boycotting Amazon. Not just due to their lack of taxes or their dodgy employment record, mainly as I believe small independent stores are much more supportive of the work that small independent musicians do.

A sad goodbye to Bath Compact Discs. You've been fab and I will miss you greatly. Thank YOU for all the support you've offered me over the years - both in stocking excellent discs and the various advice you've shared with me over the years. If anyone is looking for "a horn-playing CD salesman" (Mr Macallister is much more than that) there's him and a number of others now looking for new employment which also really sucks.